Send Help

Don’t give up on your dreams and don’t let them fester and die in the exchange for some financial security. Climg to them and chase them against all odds and common sense until they drive you to madness and murder in their pursuit. That’s the American Dream in Sam Raimi’s world, or at least within the world of Send Help. A nightmarish take on the Swept Away genre of castaway romance blended with comedy, cynicism and copious bodily fluids, Send Help is the old school Evil Dead director returned to a dazzlingly bleak and entertaining world built around the question of who is the least vile.

Don’t give up on your dreams and don’t let them fester and die in the exchange for some financial security. Climg to them and chase them against all odds and common sense until they drive you to madness and murder in their pursuit. That’s the American Dream in Sam Raimi’s world, or at least within the world of Send Help. A nightmarish take on the Swept Away genre of castaway romance blended with comedy, cynicism and copious bodily fluids, Send Help is the old school Evil Dead director returned to a dazzlingly bleak and entertaining world built around the question of who is the least vile.

Your first thought would not be mousy financial manager Linda Liddle (McAdams), a quiet cubicle worker diligently working towards her long desired promotion before going home to her pet parrot. Of course, your first thought would not be she is also a multiple-time candidate to appear on “Survivor” with a wealth of knowledge under her fingertips about taming an uncivilized wilderness if she ever found herself stranded on one. People have depths. Some people; not so much her new boss Bradley Preston (O’Brien) who has inherited wealth without working for it and has no idea how to survive in the wild (and was preparing to fire Linda). When the company plane does indeed crash in the Pacific Ocean the unlikely pair finds themselves stuck together with the possibility of something new growing between them.

And that something new is hatred and mania.

Send Help plays fast and loose with the tropes of this particular romantic fable, starting from the horrific deaths of the passengers on the plane and the increasingly gory encounters Linda survives trying to keep the pair alive initially. More importantly it immediately defines Bradley through cartoonish villainy and misogony relative to Linda’s seemingly straightforward goodness and dependability. As the days stretch into weeks, the isolation gradually reveals their truer selves, whitling away their outside pretenses – that Bradley’s shitheel exterior hides a shitheel interior while Linda’s kindness can quickly and easily transform into a hardness unwilling to take no for answer.

In different hands it could be a psychological character study, dispensing with romanticism in favor of pure nihilism as it embraces the darkest sides of human nature. None of that would be remotely as entertaining as what Raimi has put together as he turns to comedy as much as gore in a delicate balancing act most could not pull off. That is, if the word delicate could be used to describe a film where McAdams must vomit continually all over O’Brien’s face. But it’s also true, particularly during its messier third act twist when it appears rescuers may have found the island to end the pairs ordeal possibly before Linda is ready for it to.

The only thing worse than not having a dream, it turns out, is having one and watching it taken away. Within this setup, Raimi and his two very game stars who must carry almost every scene alone, play that thought out not so much to its logical conclusion as much as its most unhinged just to wink and say this is what we really want. This, in Raimiville, is the reality of the American Dream, one fueled more by monomaniacal desire than belief and which, if threatened, becomes an engine for destruction.

Just the way it should.

7.5 out of 10

Starring Rachel McAdams, Dylan O’Brien, Edyll Ismail, Xavier Samuel and Chris Prang. Directed by Sam Raimi.

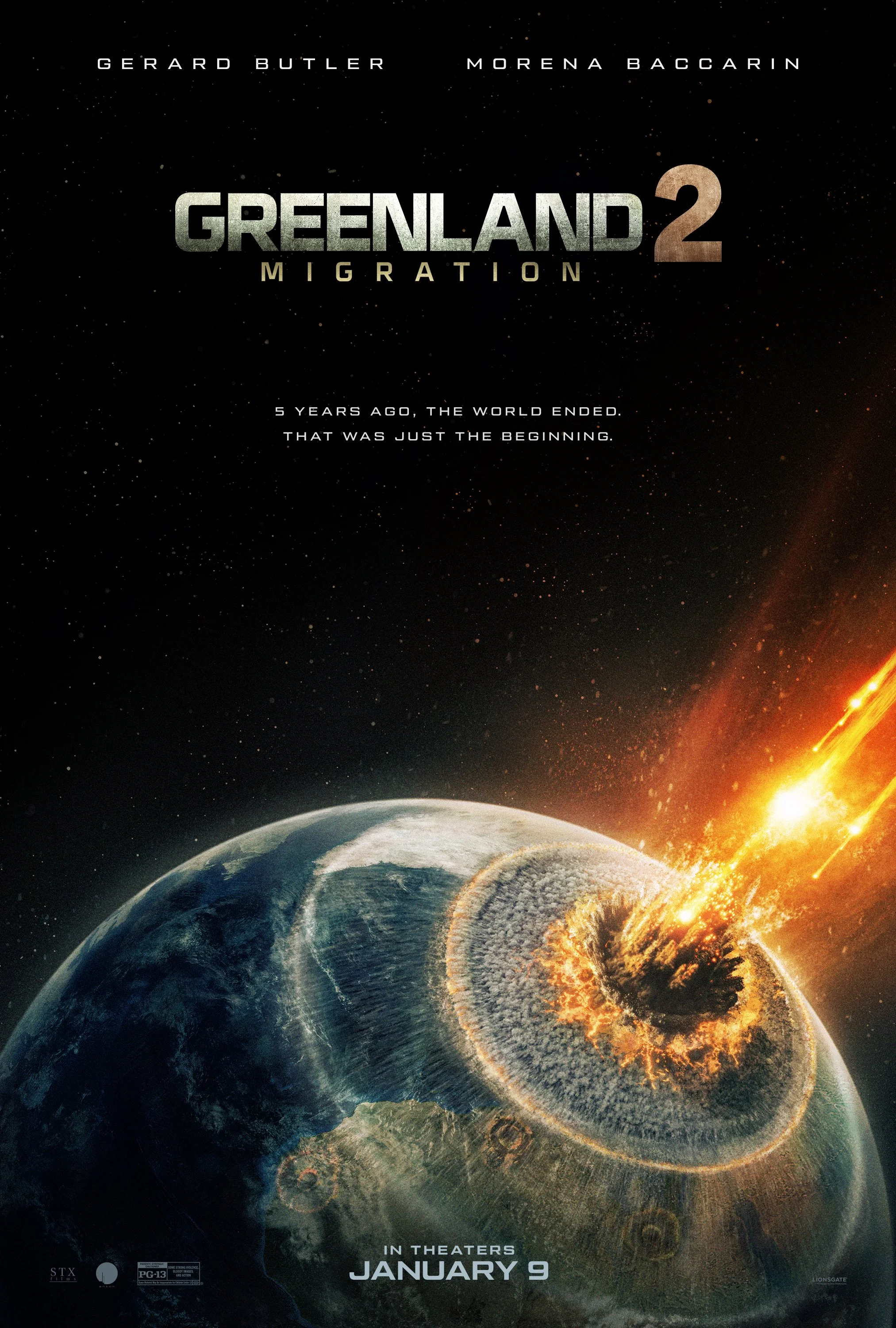

Greenland 2: Migration

When your previous film concludes with the end of the world, where do you go from there? Underground to watch the remnants of humanity slowly wither and die in Cormac McCarthy style dive into the pitilessness of nature? Or as Ric Waugh’s follow up chooses, out into the world to admit (or pretend) it didn’t actually end, it was only mostly dead and decisions for the future must be made after all.

When your previous film concludes with the end of the world, where do you go from there? Underground to watch the remnants of humanity slowly wither and die in Cormac McCarthy style dive into the pitilessness of nature? Or as Ric Waugh’s follow up chooses, out into the world to admit (or pretend) it didn’t actually end, it was only mostly dead and decisions for the future must be made after all.

Picking up five years after the first film, John Garrity (Butler) and his family have been surviving in an underground bunker in Greenland, believing they are one of the only remaining pockets of humanity left on Earth. But they may not be surviving for much longer. Radiation from the comet strike stubbornly refuses to recede, making it impossible to plant food, while increasing earthquakes threaten to make their refuge uninhabitable. When a scientist friend proposes the mind-bogglingly unlikely theory that the comet's crater in southern France may be teeming with new life—the only place where human civilization can rebuild—the Garrity clan decide they have nothing to lose and embark on the dangerous journey south.

Greenland 2: Migration is the apotheosis of the '70s disaster film brought into the 21st century. That is high praise. The end result is highly episodic and frequently chaotic, with characters and dramatic beats coming and going sometimes without rhyme or reason. Yet it never loses focus on the cost to the family or the desperation Butler faces in keeping everyone alive and safe. No matter how ridiculous some of the plot instances are (you'd think at some point they would learn to stop having picnics in fields—it never goes well for them), it never feels false or wastes time trying to become the action movie it is not.

It would have been extraordinarily easy for the filmmakers to descend into a post-apocalyptic hellscape of violence, cynicism, and brutality and call that depth. While there is certainly petty conflict—not all of which makes sense or works in any logical world-building way—more often it moves into surprising meditation on the detritus of the past and the need to move on from it. Whether they are watching a group of elites hoarding resources in their own bunkers or driving past the ruins of treasure ships on the floor of the now drained English Channel, the ruins of the past are everywhere reaching out grasping fingers to hold them back. Yes, there are dangerous people who will ambush and rob, but there are also regular people who will help a family in need rather than exploit them. It is in its frequently warm humanity that Migration separates itself from and frequently exceeds the first film, eschewing normal action-oriented thrills for something more like an episodic character drama set against the worst setting imaginable.

This isn't to say the film takes full advantage of its setup. Rather, it bounces from conflict to conflict, never giving any one of them enough time to build into something truly dangerous. Many of these story beats could have been easily expanded into a full film on their own. But frequent Butler collaborator Waugh makes the bolder choice to keep the family heading south into France no matter what, bringing each new episode to a rushed and often surprising end.

This structure gives Butler—and to a lesser extent Morena Baccarin—the opportunity and responsibility of holding the narrative together not with guns or mayhem but through the pathos of their characters recognizing the sheer odds they face. Butler's John Garrity, more than anyone else, carries the weight of the film as he eerily begins coughing up blood early on, suggesting there are no happy endings for him in the near future. Butler plays off that self-knowledge excellently, adding real weight and depth to all the twists and turns the family's voyage takes with the foreknowledge that he has limited time to succeed.

It all creates a film that is somewhat weightier than would be expected, especially for a sequel to the first Greenland. This isn't to say it has a lot on its mind beyond "you really have to do it together"—this is a surface-oriented version of depth. But it's trying in a genre and scenario where it doesn't have to and could potentially hurt itself by doing so. And mostly, it succeeds.

Butler may never get the accolades of a great actor or movie star even when he's had some excellent roles, but Migration is a film held together almost entirely by one actor and their performance—by design as much as by necessity—and that is no easy thing to do.

Greenland 2: Migration is a worthy and frequently superior successor to the first Greenland, throwing out most of the disaster film playbook to make something more episodic and introspective than anyone would have guessed, and ultimately more rewarding as well.

7 out of 10

Starring Gerard Butler, Morena Bacarin, Roman Griffin Davis, Peter Polycarpou, Amber Rose Revah, William Abadie, Sidsel Siem Koch. Directed by Ric Roman Waugh.

Avatar: Fire and Ash

It was not that long ago that Avatar creator-writer-director James Cameron (Titanic) was talking about the film series as his life’s work: an all-encompassing fantasy epic he expected to work on into his old age across four sequels which would take all of his remaining cinematic talent to bring to life. Recently, however, Cameron’s pronouncements have turned a corner, moving away from the idea of more “Avatar” films and onto other goals such as long rumored film on the nuclear attack on Japan and directing a concert film. After almost 20 years of Avatar it’s a sudden shift, one that seems to have come after watching the final cut of the third and latest Avatar installment, Fire and Ash.

It was not that long ago that Avatar creator-writer-director James Cameron (Titanic) was talking about the film series as his life’s work: an all-encompassing fantasy epic he expected to work on into his old age across four sequels which would take all of his remaining cinematic talent to bring to life. Recently, however, Cameron’s pronouncements have turned a corner, moving away from the idea of more “Avatar” films and onto other goals such as long rumored film on the nuclear attack on Japan and directing a concert film. After almost 20 years of Avatar it’s a sudden shift, one that seems to have come after watching the final cut of the third and latest Avatar installment, Fire and Ash.

Not that there is anything particularly ‘wrong’ about Cameron’s third trip to Pandora. Everything you would expect to be in an Avatar film is available in this Avatar film; dazzling world building, beautiful vistas, stoic (some might say boring) heroes and greedy but complex villains, all in service of a nature versus industry narrative ending in a fantastic climatic battle tinged in both vengeance and grief. This is Cameron’s first second sequel, despite his long and celebrated career (or perhaps because of it) Cameron has seldom returned to even his most popular narratives and never more than once and in this attempt he finds himself running into many of the problems that have bedeviled so many other talented filmmakers and make franchise film-making – particularly at the auteur level – more difficult than they may seem at first blush.

Some of that is the timing of the film. Picking up just weeks after the end of The Way of Water, and just a few years after said film emerged, Fire and Ash doesn’t have the gap of time the previous film or its narrative offered to rethink and reshuffle its status quo. No new kids or resurrected villains or sudden whale companions. It focuses more on grief and dealing with the outcomes of the previous films battles which allows for some development but also a lot of repetition. Jake (Worthington) still struggles to connect with his surviving son Lo’ak (Dalton) while protecting his family from the rampaging Quaritch (Lang) and the greedy colonizers he represents. There are additions and developments, mostly in the form of angry volcano priestess Varang (Chaplin) who raids her fellow Na’vi and has no qualms with joining with Quaritch and his human handlers, bringing him slowly into a dark reflection of the Sully clan.

But it can only go so far and the changes it can make are more decorative than they are substantive. It is hidden somewhat by changing focus, moving away from Lo’ak’s isolation to focus on human offspring Spider (Champion) and his own split between his biological father Quaritch and his chosen home. It’s the closest thing to a heart Fire and Ash but it is only one of many which keeps the film from ever truly adopting its own identity. Arcs are picked up from the previous films which, particularly within such a ponderous length, leads to characters repeating conflict and dragging out conclusion beyond any real need barring the requirement for everything to reach a head during the action climax. The classical unities were probably never thought of having to be applied to such sources and there is an argument to be made for more experimentation.

That is the one thing Fire and Ash is in short supply of. Barring an early trip on flying airships, Fire and Ash is generally content to return to areas it has spent time in before – visually and thematically – recrossing old tracks until nothing is left but a mire.

It’s as astoundingly visual as any of the films in the series. Russel Carpenter’s cinematography and WETA’s digital effects continue to combine into a rainbow kaleidoscope which, particularly in high frame rate IMAX 3D, can replicate the feel of the most astounding nature documentary ever lensed. And Cameron remains unparalleled in his ability to stage an action climax. In its first hour Fire and Ash offers three which outstrip any other action film of the year. The final climactic battle in the island’s vortex heart may be the best of the series.

For the first time, though, it all feels in service of … nothing. Like Jake’s avatar itself, it looks like one of its siblings but within it can’t help but feel artificial. Maybe, after all this time and money, it’s best for everyone to move on.

6.5 out of 10

Starring Sam Worthington, Zoe Saldaña, Sigourney Weaver, Stephan Lang, Oona Chaplin, Cliff Curtis, Britain Dalton, Jack Champion, Kate Winslet, Giovanni Ribisi, Edie Falco and David Thewlis. Directed by James Cameron.

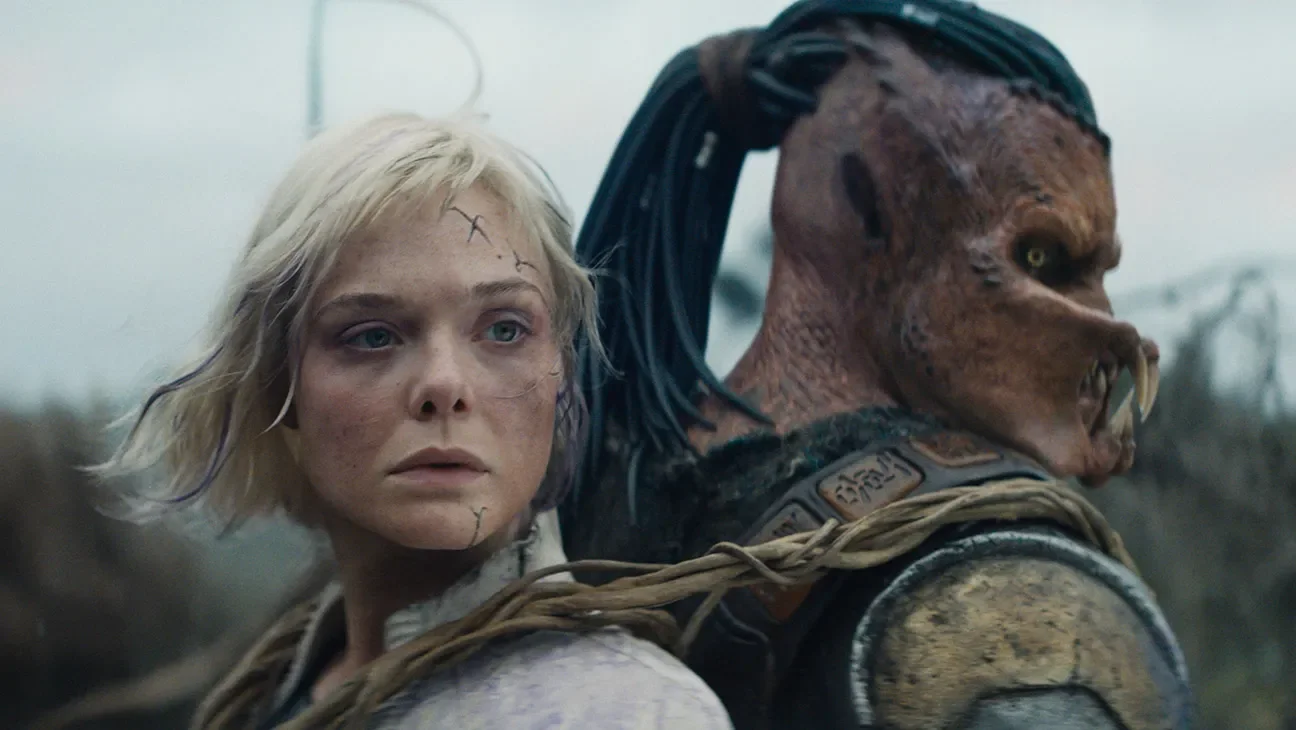

Predator: Badlands

The original Predator was the kind of classically self-contained high concept thriller that much of 80s studio filmmaking has become famous for; a retelling of “The Most Dangerous Game” focused around 80s style action heroes with the hunter replaced by an unstoppable, mandibled alien killer armed with all grains of high technology. It was both fascinatingly over the top – a meme-generator before the term was understood – and easily replicated into future installments. The alien just needed to be continuously introduced into different environments prepared to slaughter a new group of unsuspecting tough guys. Like any formula, it faces the reality of diminishing returns as there can only be so many cosmetic changes before the whole thing loses its luster. At some point it becomes either a self-parody or the Predator must win.

The original Predator was the kind of classically self-contained high concept thriller that much of 80s studio filmmaking has become famous for; a retelling of “The Most Dangerous Game” focused around 80s style action heroes with the hunter replaced by an unstoppable, mandibled alien killer armed with all grains of high technology. It was both fascinatingly over the top – a meme-generator before the term was understood – and easily replicated into future installments. The alien just needed to be continuously introduced into different environments prepared to slaughter a new group of unsuspecting tough guys. Like any formula, it faces the reality of diminishing returns as there can only be so many cosmetic changes before the whole thing loses its luster. At some point it becomes either a self-parody or the Predator must win.

Director Dan Trachtenberg (10 Cloverfield Lane, Prey) has quickly come to the same conclusion. Rather than create a blood-drenched torture fest with no survivors he has decided to pivot to a more heroic version of the monster, creating society and culture (albeit one not easily distinguishable from Star Trek’s Klingons) and understanding for them and their blood-soaked quests. The hunt is how they win their place in their society, and for young outcast Dek (Schuster-Kolomatangi), how he will win a place in his family if not his own survival. His task is to go to the most dangerous planet in the galaxy and kill the indestructible beast that lies at the heart of it – a feat no one has ever accomplished before.

It's the smart move, adding some real characterization to what had become a rote cliché. Throwing Dek onto a planet of monsters immediately transforms him into an underdog pushing himself into his own rite of passage against increasingly larger computer-generated monsters and forcing him to reconsider his culture’s views on the other living creatures of the world. An entire film in that mode, with limited to no dialogue, could have been easily sustainable but Trachtenberg immediately saddles (literally) Dek with a partner – the upper half of broken android Thia (Fanning), a Scarecrow-like lost soul searching for her ‘sister’ and her legs … whichever comes first.

Fanning is so charming and human in the role it quickly and completely makes the choice worthwhile as she allows Dek to remain laconic and mysterious while also deploying all exposition and comic relief. She is the anchor Badlands is ultimately built around having to simultaneously juggle physical comedy, pathos, genuine emotional pain and – in the dual role of her sister android Tessa – pitiless evil. She also gives Badlands an easy way out of a sticky corner. Thia and her ilk are a group of exploring androids from the Alien franchises villainous Weyland-Yutani company, still exploring the galaxy for alien lifeforms to weaponize and coincidentally giving Dek an army of human-looking villains to slaughter without the attendant blood or questions about who to root for.

(It also shows the series following Alien in its focus on AI as the true alien intelligence to be feared).

There are losses as much as gains in the approach; they mystery of the monsters takes a forever backseat in favor of their coolness and options to root for them. It also must be asked how long and far they can be pushed in this direction before uncomfortable questions (and perhaps real drama) can be found.

But in the moment none of that matters. What matters is a fresh perspective invigorating an old idea, even if only for a little while. Between Fanning’s commitment and Trachtenberg’s imagination, Predator is alive again. Let’s see how long it can remain that way.

Nuremburg

James Vanderbilt’s Nuremburg is a nearly perfect studio film. This doesn’t mean it’s a perfect film by any stretch of the imagination. It can be creaky with some obvious conflict and climax, surprises turned away in favor of setup and explication with a flair for stagey performance. A perfectly cromulent drama. But it is more than that, an exemplar of the fading studio drama form from stage design and story layout to performance and perfectly pitched music cue to push important moments. Once they outnumbered the stars in their ubiquity, the definition of what Hollywood filmmaking was and from which most of the known canon evolved. Now, nearly extinct on the big screen as movie going culture changes, they are like endangered animals encountered in the wild – both marveled at that they still exist but with a touch of melancholy that this might be the last time we see one.

James Vanderbilt’s Nuremburg is a nearly perfect studio film. This doesn’t mean it’s a perfect film by any stretch of the imagination. It can be creaky with some obvious conflict and climax, surprises turned away in favor of setup and explication with a flair for stagey performance. A perfectly cromulent drama. But it is more than that, an exemplar of the fading studio drama form from stage design and story layout to performance and perfectly pitched music cue to push important moments. Once they outnumbered the stars in their ubiquity, the definition of what Hollywood filmmaking was and from which most of the known canon evolved. Now, nearly extinct on the big screen as movie going culture changes, they are like endangered animals encountered in the wild – both marveled at that they still exist but with a touch of melancholy that this might be the last time we see one.

Even the subject matter is perfect; Hollywood has produced more films about the Nazis and World War II than almost any other subject since the event occurred. Can anything more be said about them through this particular lens and/or transplanted onto our modern world? We will certainly know one way or the other by the end; in this case by the end of the famous Nuremburg trials. The second major studio take on the event follows less the legal structure and indictments of the trials and more the interaction of the Allied psychiatrists (Malek and Hanks) tasked with analyzing this strange group of human monsters for fitness to stand trial and find out what, if anything, led them to do what they did and whether they felt any guilt at all.

These types of films tend to be performance showcases and Nuremburg is no different. Essentially a two-hander between Malek’s Kelley and Crowe’s Göring, it’s ultimately not much about the psychology of the Nazi’s or even the difficulties of the trials (which can make them seem tacked on when they appear) as much as it is Kelley’s arrogant obliviousness of the reality of the men he is chronicling amid his certainty he can understand them. Unable to understand how such mostly normal seeming individuals could have done such terrible things he unconsciously pushes the thought aside until he is unable to see any forests at all anymore, only trees. It’s the sort of cracking restraint Malek excels at and he fits the role like a glove, though much of the success comes from performing opposite a Crowe who is more restrained than he has been in years. Göring’s madness instead pierces always from his eyes but goes no further. It's no accident Nuremburg is most alive and has a character of its own when it’s left to just the two of them.

Outside of that Vanderbilt’s script is a more standard dramatic affair, attempting to make larger points about the trial’s focus and the importance of them to prevent the recurrence of the defendants’ crimes – not to mention how easily it is for such crimes to appear in other nations – with strained monologues and more standard courtroom sequences. The dramatic impetus must then be some sort of confession by Göring on the witness stand, a feat left to chief prosecutor Robert Jackson (Shannon) guided by Kelley’s work. Can the psychiatrist be trusted or has he grown to close to his subjects to see the truth?

It's fine, if unremarkable; and yet amazing in its complete adequacy. Even ten years ago it would have been one of dozens of like-minded and toned films coming important elements in the most reductive way possible, the end result of surviving the studio process. Now so few can even attempt such a process; what comes out the other side is less static melodrama and more artifact of the past, out of style even at its creation as filmmaking and filmmakers try to figure what the new version of the form will be. In that sense it should be intensely studied and treasured before we don’t get any more like it.

6.5 out of 10

Starring Rami Malek, Russell Crowe, Leo Woodall, John Slattery, Mark O’Brien, Colin Hanks and Michael Shannon. Directed by James Vanderbilt.

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale

Things change. The original television version of Downton Abbey was about many things, but like all period drama it was ultimately it was showing us what we had come from to better know what we were now. Downton Abbey the series is no more immune to that than anything else; viewers of the original would be hard pressed to recognize it in Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale. Much of what it once was – social friction, reserved romance, repressed melodrama – hasn’t been jettisoned so much as concluded. The daughters married, most of the servants settled, the estate ordered; short of repeating old stories, there’s little left to do. What’s left is less a finale than an epilogue.

Things change. The original television version of Downton Abbey was about many things, but like all period drama it was ultimately it was showing us what we had come from to better know what we were now. Downton Abbey the series is no more immune to that than anything else; viewers of the original would be hard pressed to recognize it in Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale. Much of what it once was – social friction, reserved romance, repressed melodrama – hasn’t been jettisoned so much as concluded. The daughters married, most of the servants settled, the estate ordered; short of repeating old stories, there’s little left to do. What’s left is less a finale than an epilogue.

Everyone is here of course, and then some, but also not to the level you would expect. Most of the series familiar faces are pushed to mere cameos, reminding us they exist but also that their stories are spent. The classic “Upstairs, Downstairs” braid gives way to a narrower focus on the avuncular Robert Crawley (Bonneville) and his wife and daughters as they traverse the handoff of ownership of Downton to Lady Mary. The transition is jeopardized when Lady Cora's (McGovern) brother Harold (Giamatti) informs her that much of the family capital has been lost due to bad investment. As the spring festival and the time for Lady Mary's ascension draws near everyone hunts for a solution, but the drama never crests; the world’s formality calcifies into formula.

It didn't have to be this way, there are tendrils of the old Downton in view even if they are batted away and brushed under the carpet to keep out of view. As much as Downton lived and breathed on the social dynamics between the Crawley’s and their servants, it was also the melodrama of the romances each group suffered which powered the old show. Creator-writer Julian Fellowes still has that old instinct as Lady Mary’s ill-conceived marriage to racing enthusiast Henry Talbot crumbles around her, ending in divorce and social castigation. Where the old Fellowes would have made that the centerpiece of his plot, with Mary and family deciding if the exile was worth the end of the pain while the family servants looked on and gossiped about it despite their own internal stripes, this version wraps it up off screen before the film has even begun.

In theory that is to spend more time focusing on the social fallout and how that may jeopardize Robert’s plan to hand control of the estate to Mary and the next generation. And that may have been the original idea but in between came the the realization that there were so many other things which needed to be dealt with like kitchen servant Daisy becoming part of the spring festival planning committee and the introduction of newcomer Gus Sandbrook (Nivola) and his plan to restore the family fortune. Mary's social stigma is reduced to an excuse for Lady Edith (Carmichael) to plan a grand party in order to invite back all of the family members and former servants for one last time in front of the camera.

It's as beautiful as ever and the hints and nods of great societal change are still there they are merely hints and nods. Downton Abbey is a shadow of its former self not just because times changed for it but because times change for us. Rather than use the past as a reflection on today the way the original series did the best anyone can muster in the Grand Finale is a limp wave of farewell and they hope that a dash of nostalgia will make it go down well. It probably is all that an old fan of the series could want; one last short romp and, short of death, a final stroll into the sunset for the old series. But like watching a beloved athlete in their final season, it’s impossible not to compare what is to what was.

6 out of 10.

Starring Hugh Bonneville, Michelle Dockery, Elizabeth McGovern, Laura Carmichael, Alessandro Nivola, Paul Giamatti, Jim Carter and Joanne Froggatt. Starring Simon Curtis.

Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba – The Movie: Infinity Castle

As a child, diving into long running series had no terror or qualms. Chapter 234 may as well have been chapter one. The high numbers and rich history were not a roadblock but an invitation to gather as much as possible through context clues with a confidence boarding on delusion that the major points would shine through, and missing backstory could eventually be sussed out.

As a child, diving into long running series had no terror or qualms. Chapter 234 may as well have been chapter one. The high numbers and rich history were not a roadblock but an invitation to gather as much as possible through context clues with a confidence boarding on delusion that the major points would shine through, and missing backstory could eventually be sussed out. Somewhere in the winding path to adulthood that view is lost; late chapters become a warning instead, of a story or characters to layered or developed to understand short of going back to the beginning and starting fresh and who has the time for that? Like the demons and demon slayers of Koyoharu Gotouge’s popular manga, our own growth has cost us a piece of ourselves.

If you want to try and push back the hands of time, you could jump feet first without preparation into Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba – The Movie: Infinity Castle. Not because it will generate a fuzzy recollection of what childhood was like in the manner of a Pixar film and more the way it drops you into a long running narrative of many characters without explanation or lifeline. Demon’s need slaying and it’s sink or swim. This much is clear: the Demon Slayer’s are an organization of highly trained martial artists studying to fight and kill supernatural menaces preying on mankind. Their key target is an ancient demon lord named Muzan who has retreated to an impossible fortress which seems to go on forever. The Demon Slayers have somehow invaded it in an attempt to find and dispatch Muzan for good (usually requiring a decapitation to achieve), though they will have to fight through many of his strongest general’s first.

This much more is clear – this is not just the middle of larger narrative but only one part of that middle. There is no resolution to be had here, either narrative or thematic. Despite dropping in media res and continuing on for more than two and a half hours Infinity Castle continues on to its next chapter with a breeziness and lack of concern no film outside of the genre could hope to achieve without audience revolt. The temptation to stand up at the end and cry “that’s it!” is strong, but also not entirely warranted as there is some meat to be had even as it spends tremendous amounts of time on specific characters history and nature after their key conflicts have been resolved.

Most of that history revolves around pain, and a related obsession with strength. Not every Demon Slayer in the group gets much in the way of focus to set them apart. Most of Infinity Castle’s focus is only a handful battling their own literally personal demons; primarily orphan warrior Shinobu (Harlacher) finally coming face-to-face with the monster (Fu) who killed her older sister, young swordsman Zenitsu facing his brother-turned-demon jealous of Zenitsu’s relationship with their grandfather and Tanjiro’s (Aguilar) failures against an unstoppable martial artist (Dodge) who can survive anything thrown at him. The one key line connecting all of them is pain, either from loss or from jealousy or some other internalized fear, leading to a need to grow strong enough to avoid such pain ever again. It’s a unique reaction both hunters and hunted embrace and in their turn leads them to hurt others the way they’ve been hurt. Demons aren’t demons in Demon Slayer; they’re pain and the core of cycles of abuse which can’t be ultimately vanquished. Only faced and at some level only dealt with by ignoring them. Those who can’t, will ultimately die.

Where it’s leading is impossible to say (unless you’ve already read the books) and it’s hard to say yet if there’s more to the series than these general ideas which are repeated in long, drawn out character moments for clarity. In between there is some startling beautiful animation, from the castle’s fascinating design to the chaotic fight sequences, which may be primarily surface oriented but offers enough pleasures to get around that. There’s no doubt there will be more – there is still plenty of plot out there – but will there be more amid the more? Time will tell but it’s a good start so far.

6 out of 10.

Starring Zach Aguilar, Abby Trott, Aleks Le, Bryce Papenbook, Brianna Knickerbocker, Zeno Robinson and Johnny Yong Bosch. Directed by Haruo Sotozaki.

F1

Joseph Kosinski’s F1 is incredibly smooth, as well oiled a professional piece of filmmaking as you will find, a modern day Days of Thunder shorn of all rough edges so that it can cut through the air like a knife.

Slow is smooth and smooth is fast, the old saying goes. Joseph Kosinski’s F1 is incredibly smooth, as well oiled a professional piece of filmmaking as you will find, a modern day Days of Thunder shorn of all rough edges so that it can cut through the air like a knife. In the process it sometimes cuts through logic, originality or characterization but it’s infuriatingly entertaining it’s easy to ignore how straightforwardly uninterested its screenplay is in human beings. That’s not what anyone is really here for; they’re here for Formula One cars sliding around tracks at 200mph and Brad Pitt’s movie star charisma, neither of which have anything to do with being human. But given the right place and the right context, they’re just about the only thing that matters.

It’s much the same for Sonny Hayes (Pitt), an itinerant race car driver who only seems to make any sort of sense behind a steering wheel. Moving from track to track as hired gun for anyone who needs a killer, Sonny barely speaks to regular people or understand what makes them tick – probably because he barely understands himself. But once behind the wheel of a car, or arguing with another driver, and all questions and concerns fall away as embraces something he does understand. After years of drifting he finally gets to put that talent to the test when his old teammate (Bardem), now Formula One team owner, asks him to do the impossible: lift the worst team in the division from last place, past the best drivers in the world, and win at least one Formula One Grand Prix.

And in the process, translate the thrilling speed of the race into a cinematic spectacle in a way film has seldom captured. That’s a tall order, for Sonny and for the filmmakers.

Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix has rightly been hailed for decades as the definitive car race film. The way it put cameras, and through them the audience, down into the point of view of the cars racing along the tarmac amongst stark cutting created a unique view of speed that quickly became part of the car chase lexicon, lending power to its melodramatic elements. Kosinki’s approach is not any different, just smoother, taking all of the tools of the last 60 years to bring us more into the middle of the race than ever before. He realizes, as Frankenheimer once did, that the human beings don’t matter because the creates the audience wants to be are the metal beasts careening around the tarmac within inches of one another, always risking disaster. The personal trials of Sonny to win one last race or rookie Joshua Pearce (Idris) to live up to his potential pale in comparison to that, which is why it’s perfectly fine that they are as thin as paper or lacking any sort of emotional connection.

What it lacks in interesting storylines (the patchwork framework of F1 is the desiccated corpse of every sports movie to date pinned together with tropes and the kind of dialogue that survives through studio development) it makes up for in pure charisma, both from the cars and from Pitt’s old fashioned movie star mastery. F1 is the kind of film made for a Hollywood star to sit in a car, look cool and charm his way through scenes. That’s not a bug, it’s a feature; it was done that way for so long because it works, even if we’ve forgotten. It worked then and it works now. No, F1 doesn’t have a core of internal drama or character realization adding to the onscreen fireworks the way Kosinski’s superior Top Gun: Maverick did. It has a Formula One driver who lives in a Volkswagen Minibus and has a gambling problem, and for a film like F1 it really doesn’t need anything more.

The genius of F1 lies not in what it aspires to be, but in what it refuses to pretend it isn't; it is here to deliver one specific experience: the vicarious thrill of speed, danger, and effortless cool. Kosinski understands that sometimes the most honest thing a film can do is embrace its own superficiality, to polish that surface until it becomes a mirror that reflects our desire to be somewhere else, someone else, moving faster than humanly possible. In an era where blockbusters often buckle under the weight of their own self-importance, F1 succeeds by staying in its lane, never apologizing for being exactly the kind of star vehicle that Hollywood used to build with confidence. It's a machine built for pleasure, nothing more and nothing less, and like the best machines, it does exactly what it was designed to do.

7.5/10

Starring Brad Pitt, Damson Idris, Kerry Condon, Javier Bardem, Tobias Menzies, Kim Bodnia, Sarah Niles and Will Merrick. Directed by Joseph Kosinski.

Jurassic World Rebirth

Moreso than any recent big studio film, Jurassic World Rebirth reeks of the studio requirement. At points it is possible to see the list of elements believed to be necessary for a Jurassic Park/World film.

During World War II, Allied Forces built airstrips around Melanesia as staging posts for fighters and bombers to refuel and resupply for long distance combat against Japanese forces. To the indigenous tribes living on the islands it was as if the gods themselves had come down, literally flying down from the heavens and leaving artifacts of their passing behind. Such was the impact of these moments that after the war, when the military had left and no more cargo came to the islands, some islanders began building mock airstrips, control towers and even planes out of the bamboo, wood, reeds and other elements they had at hand, trying to bring the precious cargo drops back by replicating the surface conditions of their arrival without ever comprehending what they had witnessed or how it happened the way it did.

One imagines a similar reaction from a generation of filmmakers watching Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park when it first came out (or George Lucas’ Star Wars before it), filled with awe at the cinematic spectacle but unable to understand what was going on beneath the surface to make it work the way it did, just knowing they wanted to experience it again. Certainly a generation of studio executives did. And the result is the cargo cult version of the original: a replication without spirit or soul, trying to call back the original through ritualistic adherence to the forms rather than thought or creativity.

Moreso than any recent big studio film, Jurassic World Rebirth reeks of the studio requirement. At points it is possible to see the list of elements believed to be necessary for a Jurassic Park/World film. Dinosaurs, yes obviously, but also the remote island location, children and family members becoming stuck on the island for extra jeopardy, evil corporate villains willing to sacrifice anything for the wealth living dinosaurs could bring, dangerous flight among stalking predators through an empty laboratory … it’s even more of a complete recreation of the original than the first Jurassic World was. Gone is any attempt to move the threat to a new milieu or come up with new ideas. Over the last five years al of the dinosaurs roaming the wild at the end of the previous film have died from various environmental ailments, the survivors retreating to remote equatorial islands and jungles to live out their remaining days … including an island off the coast of French New Guinea which just happened to once host a secret Ingen dinosaur lab.

What comes from there doesn’t need much explaining because if you’ve seen any Jurassic Park film, you have seen Rebirth. Director Gareth Edwards and writer David Koepp (returning to the franchise for the first time since The Lost World) are solid pros who approach the material in exactly that manner with fun, competent set pieces and no sense of danger or wonder whatsoever. Moments here and there standout, particularly an all to brief flight through a swamp with a lit flare that feels like a lost element of Vittorio Storaro’s Apocalypse Now shots except with a giant dinosaur entering the frame. Moments like that can’t really change things for Rebirth, nothing can, but they can give at least the idea that a human being is thinking about these things even if they are not in control of their own fate.

More even than the cargo cult replication, Rebirth feels like the filmmaking generated by AI that the industry has been worrying over for so many years now. All of the ingredients of a Jurassic Park film have been fed into the computer and competent and soulless reproduction has come out, one incapable of holding new ideas, only of endlessly replicating what it has already been shown. At this rate Hollywood does need to worry about AI doing this to the business, they will have already done it themselves.

4 out of 10

Starring Scarlett Johansson, Mahershala Ali, Jonathan Bailey, Rupert Friend, Manuel-Garcia Rulfo, Luna Blaise, David Iacono and Audrina Miranda. Directed by Gareth Edwards.

Wick is Pain

In an era when Hollywood chases sprawling cinematic universes with almost manic devotion, the John Wick movies emerged as something like a modern unicorn—a lean, star-driven vehicle built around a premise many insiders dismissed as silly (an ex-hitman avenging his dog) and devoid of any tie-in comics, spin-off series, or shared-world machinations.

In an era when Hollywood chases sprawling cinematic universes with almost manic devotion, the John Wick movies emerged as something like a modern unicorn—a lean, star-driven vehicle built around a premise many insiders dismissed as silly (an ex-hitman avenging his dog) and devoid of any tie-in comics, spin-off series, or shared-world machinations. From the outset, co-directors Chad Stahelski and David Leitch operated under a single, uncompromising mandate: make a cool action film. No velvet-gloved marketing campaigns, no executive directives to broaden the franchise’s scope—just unvarnished, practical spectacle.

Wick is Pain refuses the glossy promotional spiel in favor of a warts-and-all vérité chronicle. Rather than lionizing actors or department heads, the documentary hands the microphone to the producers and directing duo who pushed the series into existence, laying bare the struggles to develop the material, to explain to others, to find all of the dollars needed to keep it alive. It’s a rare glimpse into Hollywood’s development hell—an unedited odyssey that reminds us how perilously close many of our favorite movies once were to never existing. This candor, in itself, becomes an act of defiance against an industry that often rewards safety over originality.

We first meet Stahelski and Leitch as martial artists slowly working their way into the world of stunt men, in Stahelski’s case in the harrowing aftermath of Brandon Lee’s tragic death on The Crow. Eventually that difficult beginning led Stahelski to meeting Leitch and, more fatefully, Keanu Reeves on the set of The Matrix, where he served as Reeves’s primary stunt double complete with a broken knee and multiple other injuries. These formative years, captured without filter, underscore the doc’s thesis: that every spectacle is rooted in personal pain and ambition.

And the toll is as much emotional as physical. The documentary captures financiers who chase only safe bets, studio executives who label the concept “unproven,” and film buyers who blink at the sight of a hitman seeking revenge for his murdered dog. And even after the money does flow, the film itself must be created by two directors learning the craft as they go. Both Stahelski’s marriage and his working relationship with Leitch end up being casualties to the process as he must make decisions on where to focus—on John Wick or on anything else. And the answer, for the better part of a decade, is Wick is Pain.

From this ordeal John Wick did more than break through; it exploded into a phenomenon. Wick is Pain tracks that ascent as it happens and affects all attached to it, but success brought its own crucible. Suddenly, the question was no longer “How do we make one cool film?” but “How do we outdo ourselves next time?” Sequels demanded bigger villains, deeper mythologies, and heart-stopping stunts. The purity of the original manifesto—make the coolest action movie possible—yielded to the inexorable demands of franchise maintenance. This shift, rendered poignantly on camera, highlights the paradox of victory: the dream you once chased becomes its own constraint.

Arguably the documentary’s most harrowing moment arrives mid-film, when a stunt on John Wick: Chapter 3 goes catastrophically wrong. A performer flies across a ledge and crashes attempting John’s fall from a building at the end of the film. Despite the obvious pain and blood he immediately plans to go again, and no one from production stops him, despite a high likelihood of suffering at least a concussion if nothing else. One clear hallmark of the series is that it is made by stuntmen with all that entails. The familiar tagline that Wick is Pain is not just a brag, it’s also a warning. The filmmakers’ insistence on “doing it practically” imbues each sequence with visceral authenticity—and it raises urgent ethical questions: what is the human cost of chasing realism in an age of digital illusions?

Stahelski and Leitch’s candidness feels almost radical in an industry built on spin. Whether born of naïveté about its impact or of a deliberate decision to expose the mechanics of creation, their willingness to reveal bruises, blood, and shattered egos cracks Hollywood’s polished veneer and invites us into the backlot trenches. Wick is Pain does more than celebrate a landmark action franchise; it compels us to acknowledge the human grit and yes, the very pain, that fuels our escapist thrills.

Ultimately, the documentary delivers a sobering reminder: the slickest, most electrifying films are rarely born of untroubled bliss. They emerge from uneven dreams, bruised bodies, and the relentless grind of an industry caught between commerce and creativity. Wick is Pain honors both the triumph and the sacrifice behind modern action filmmaking in a way that should at least keep us asking how much we want what we’ve been given.

7.5/10

Starring Keanu Reeves, Chad Stahelski, Basil Iwanyk, David Leitch, Tiger Chen and Derek Kolstad. Directed by Jeffrey Doe.

The Last Rodeo

The Last Rodeo is the standard of studio-driven character drama we claim no one gives us anymore, the middle-of-the-road, star-driven drama that wears its heart on its sleeve.

The Last Rodeo is the standard of studio-driven character drama we claim no one gives us anymore, the middle-of-the-road, star-driven programer that wears its heart on its sleeve. This feels less like nostalgia and more like a quiet rebuke of contemporary cinema’s prevailing priorities. In invoking a vanished era of filmmaking, The Last Rodeo simultaneously gestures toward a tradition of unadorned sincerity and invites us to wonder how much has been sacrificed at the altar of spectacle.

It doesn’t have any large philosophical ideas or complex structures it wants to show us, nor is it a repetition or replication of some existing book, show or film. It is free from the shackles of the dreaded “IP.” It asserts originality as a virtue, daring to stand on its own narrative legs.

It’s that rare bird, the complete original, at least insofar as it exists entirely unto itself. Granted, ‘originality’ can mean a lot of different things. The specific content is a well-trod story of loss, hope and determination. Which is fine, that’s what the mid-budget Hollywood drama has always been. It’s just become so rare to see we’ve forgotten what it looks like. In reminding us of this familiar terrain, The Last Rodeo acts as both homage and hypothesis: can a film of such simplicity still move us in an age of commercial spectacle? Its confidence lies in that very question.

It’s the story of Joe Wainwright, a former champion bull rider who had to give up the sport after one bad fall too many and but has found some peace living on his daughter’s farm and helping raise her son. When a sudden surge of symptoms reveals the boy has an aggressive brain tumor needing immediate surgery—surgery the family cannot afford—Joe’s quiet life shatters. With time running out and few options on the table, Joe risks reopening optional and physical wounds when he enters the open bull-riding championship looking to claim the prize of $750,000 and keep his grandson alive … even if it kills him. Here, the narrative’s stakes are laid bare without artifice: love versus mortality framed in the rodeo arena. Its emotional pulse emerges from this collision.

Co-written and starring Neal McDonough, The Last Rodeo is a proficient A-to-B story with few surprises or unexpected turns, primarily because it doesn’t need them. Under the watchful hand of experienced journeyman producer-director Jon Avnet (Fried Green Tomatoes, The War, Up Close & Personal), The Last Rodeo professionally and efficiently moves through its paces, focusing on the pure relationship and small character moments that has always been the hallmark of these kinds of movies. In that sense Avnet is the perfect choice, an experienced craftsman of exactly the kind of movies modern Hollywood doesn’t make anymore and which a younger, slicker director may not have known what to do with. It’s easy to imagine him resting in a glass case with a hammer nearby marked “break in the case of classic mid-budget studio drama.” Avnet’s touch is both assured and discreet, allowing scenes of quiet desperation to resonate without superfluous ornamentation. His direction avoids the temptation of visual grandstanding and instead cultivates a sense of lived-in reality.

actor In that sense Neal McDonough, who also co-wrote the script with Avnet, is the perfect leading man for The Last Rodeo. An excellent with real prospects as a young man, he has gradually moved into more and more character work and type-cast villains across film and television -- rolls he plays with aplomb, but which never quite seem to get the depth of performance he is capable of -- as his career winds on. It’s easy to see a lot of Neal in Joe and vice versa, both grabbing at the one big chance to show what they’re capable of and how underestimated, by life and peers, they have been. McDonough channels this personal resonance into a performance that is at once guarded and raw, every measured gesture suggesting layers of regret and resolve beneath the surface.

He’s aided by a sturdy cast including Mykelti Williamson as his best friend called in to aid him in his quest, For All Mankind’s Sarah Jones as a daughter torn between hating what her father is doing after seeing how it almost killed him and grasping at any hope for her son, and Christopher McDonald as the head of the Professional Bull Riders Association who must pull some strings to get the aging star back in the saddle. And sturdy is probably the best way to describe The Last Rodeo. It goes about its business with no muss or fuss, from Denis Lenoir’s straightforward photography to its casts business like work. None of this is a negative, some films feel like they've forgotten how to do this. The visual austerity—wide shots that root characters in their environment, close-ups that capture unguarded emotion—echoes its narrative restraint. It trusts the audience to find wonder in the everyday details.

More importantly it shows Avnet’s experience as he understands exactly when to get out of his cast’s way. The tough moments when Joe and Charlie confront old pains with one another, Jimmy’s concern for Joe fighting with his need to put on a good show, Sally’s fear for both her father and her son - The Last Rodeo is a film filled with humanity played by actors who have too often had to dig into excess. Watching them just be people is a revelation, and hopefully not for the last time. In these scenes, the film transcends its own modest ambitions, revealing how deeply unvarnished performances can cut when given room to breathe.

The only outcast is professional bullrider Daylon Swearingen who, even playing a professional bullrider, is bland and unconvincing. He is in that sense the equivalent of every professional athlete called upon to make a cameo in a film as themselves.

Is it the greatest drama of the year or some transformative experience? No. But one of the things we've forgotten is that not every film needs to be. Some just need to be The Last Rodeo. In accepting its modest goals, the film reclaims a lost art: the ability to tell a heartfelt story without apology. In an age starved for sincerity, that may be the most radical act of all.

7.5/10

Starring Neal McDonough, Sara Jones, Mykelti Williamson, Christopher McDonald and Graham Harvey. Directed by Jon Avnet

From the World of John Wick: Ballerina

The point of a derivative work is to retain and contain as much of its progenitor as possible; it shouldn’t surprise that Ballerina, the inaugural spin-off of the successful John Wick franchise, is lavish tableau of orchestrated violence encased by a gossamer plot and singularly focused characters. It was ever thus.

The point of a derivative work is to retain and contain as much of its progenitor as possible; it shouldn’t surprise that Ballerina, the inaugural spin-off of the successful John Wick franchise, is lavish tableau of orchestrated violence encased by a gossamer plot and singularly focused characters. It was ever thus.

The series has grown in both logistical and philosophical ambitions as it has gone on, somewhat transcending its original conceit, so it’s easy to forget it started off with a joke: a hitman goes on a roaring rampage of revenge after the mob kills his dog. (Does anyone even remember Wilem Dafoe was once a major character in this). The silliness was part of the recipe and granted license to ignore the reality that it was an action movie, not only offering the barest of motivations for its set pieces but scoffing at the expectation that should offer any. And it worked, so why expect more from its offspring when that is specifically against the purpose of the spin-off to begin with: the return of familiar milieu with a replacement of characters, ideally unnoticed in their exchange. If you like hot dogs you’ll like corn dogs, they are essentially the same.

If only it were so easy.

Successful franchises are usually based around charismatic actors portraying dynamic or at least interesting characters; the very definition of lightning in a bottle. Attempting it twice tends to increase your odds of being struck by the lightning bolt rather than snaring it. John Wick power adroitly wielded Keanu Reeves’s taciturn stoicism and the surgical precision of its choreography as its twin pillars. Replicating that with a fresh protagonist—Ana de Armas as a wrathful assassin searching for her own path to freedom—and a new director, Len Wiseman (Underworld), is a gamble. Ballerina attempts it with all the hallmarks of the Wick universe but also embracing its own droll humor, offering glossy visuals and gleeful excesses that reveal both the pitfalls and the potential of trying to extend a beloved action template.

Occurring ‘somewhere’ between John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum and John Wick: Chapter 4, we find Armas’ Eve as the only survivor of an assault on her family, rescued by the eternally urbane Winston (McShane) and sent to Angelica Huston’s mysterious Director to be raised as an assassin for her new family, the Ruska Roma—mirroring Wick’s own ascension. When a contract (Reedus) turns out to be hunted by the same cabal of assassins who orphaned Eve, she renounces her adoptive kin to find answers about why she was orphaned and the man (Byrne) responsible. And if she gets to dish out healthy helpings of revenge in the process, so much the better.

What follows is a slow dance through Europe as Eve fights off rivals and follows a breadcrumb trail to her quarry’s mountain enclave, but Ballerina cares about that as little as we do. The point is the fight, often erupting spontaneously into a rousing chorus of strange beauty like stumbling upon the Aurora Borealis. Despite a new director at the helm Ballerina remains tethered to the franchise’s hallmark aesthetic—hyper-choreographed carnage against a pristine, almost antiseptic backdrop positioning Eve like a surgeon in an operating the theater. Wiseman maintains continuity but doesn’t mimic. He peppers Ballerina with humor, embracing sight gags and playful puns with genuine glee: a TV changing channels as Eve pummels a foe with the remote control; a helpful informant who must “be frank,” his name tag a winking signpost, enemies digging through a pile of plates looking for a hidden firearm. These flourishes do more than lighten the mood; they crystallize Wiseman’s willingness to “cast off reality” and go full-tilt toward the ridiculous. Think the various sword and gun fights in the John Wick films were dynamic, creative and all around cool? What if they replaced the swords with grenades, or the climactic pistol duel was recreated with flamethrowers? Ballerina never apologizes for its cartoonish excess; it revels in it, daring audiences to suspend disbelief for spectacle.

Wiseman also brings a polished, studio look to challenge the main series more formalized gleam, but that’s about where the challenging stops and the impediments of replication begin. John Wick’s kinetic bravura was undergirded by an existential undercurrent—its protagonists cognizant of the futility of their odyssey. Ballerina is not looking for that level of insight, it stops at the surface and delves no deeper, offering little options to generate its own identity. Its reliance on familiar leitmotifs—well-worn locales, appearances from familiar faces including a final performance from Lance Reddick, and a more substantial presence from Keanu Reeves than anticipated—functions primarily as a balm for nostalgia. As functions of comfort they work exactly as intended, particularly for Wick who – shed of the need to carry loss and obstacle as a core protagonist – is re-created as the unstoppable monster his enemies have always described. These gestures serve as reminders that this universe remains, at its essence, another’s. Ballerina never severs its umbilical cord; nor does it aspire to, content instead to occupy a stylish interim.

All of which underscores a paradox: Ballerina is demonstrably superior to much franchise ephemera—its choreography remains a tour de force, and its visual excesses can dazzle—but it also reaffirms that further innovation, and soon, will be needed if the John Wick descendants are ever going to survive on their own. In its current incarnation, Ballerina is an exhilarating interlude, yet it is incomplete; a sumptuous appetizer that hints at the ambition of a full-course feast yet unrealized.

7.5/10

Starring Ana de Armas, Anjelica Huston, Gabriel Byrne, Ian McShane, Lance Reddick, Norman Reedus and Keanu Reeves. Directed by Len Wiseman.

The Passengers

Thomas Mazziotti’s The Passengers unearths archival footage of 90s New York to reflect our collective past, but offers less novel self-reflection and more of an exposé on the personalities you find when you advertise in The Village Voice.

Thomas Mazziotti’s The Passengers unearths archival footage of 90s New York to reflect our collective past, but offers less novel self-reflection and more of an exposé on the personalities you find when you advertise in The Village Voice.

That sounds like a burn, but it’s not. Part of the allure of the metropolis is the kaleidoscope of grotesques we imagine lurking around each corner. Spotlighting the strange and self-absorbed isn’t solely a function of Mazziotti’s focus on the unusual and idiosyncratic over anything like an “everyman’s” experience. He’s certainly not the first documentarian to make that choice and he won’t be the last; it’s the reality of working in an ultimately narrative form as opposed to the recitation of quotidian experience. And it’s possible that these are the “everyday” of New York: a coterie of wounded, self-absorbed individuals drawn by the city’s whispers of fame, fortune and significance – and ultimately stranded there. Individuals who dwell on the pains done to them in youth, or who think continuously on the pain they actually enjoy and want to inflict on others, combined with a fear of boredom and lack of clarity on what to do about it. It is, if nothing else, an arresting cross-section of humanity.

Not that everyone interviewed fits into that mold. Some exhibit a broader awareness of the world, harboring a creeping, existential dread of life and its relentless onward march. A woman on the train meets an elderly survivor of the Pearl Harbor attacked and is moved to reflect on what it must have been like to live at that particular moment without realizing what it was. At the same time another interviewee reminisces on a dead body they saw on the street, someone who will never live long enough to witness epochal world events and the pass their stories on to their grandchildren or a young passerby.

It doesn’t particularly hide Mazziotti’s hand, he is fond of flashing updates to past important events as a reminder of what has and hasn’t changed even as life has gone on: the aforementioned Pearl Harbor attack, the death of Martin Luther King, Jr., Ronald Reagan and other things once mentioned in a Billy Joel song. It opens the question more how many of the interviews included were picked for their uniqueness and entertainment value, providing us our own escape from the world flowing around us and our own potential ennui, rather than what that might say about life at the time. And if that was the focus The Passengers succeeds. It’s compulsively watchable and there is an unmistakable feeling of authenticity even as deliberately bizarre and off-putting as its subjects can be.

It does raise questions about the world around those lives relative to events they are compared to, explicitly in the film itself and implicitly in the era in which we are viewing them. Opened up in 2022, the contents of the time capsule are coming to us in a post-Covid world after living through legitimately world changing events every bit as momentous as the ones in Mazziotti’s various title cards. By comparison, the world of the subjects, New York 1992, is more settled and mundane, almost banal, which says a lot about how inwards focused its view was at the time.

Perhaps a better version of this would have been to replace the footage in the time capsule with interviews conducted today to let a future generation see what we were like in the aftermath of a global upheaval. And maybe they'd discover the same thing The Passengers does, that we were always this self-absorbed and maniacal, we just notice it more now. In its reflexive exposure of curated oddity, its juxtaposition of private confession and public history, and its unflinching gaze at existential paralysis, The Passengers emerges not merely as a nostalgic artifact but as a searing critique—an elegy for a city and a medium that both seduces and emaciates the soul.

7.5 out of 10

Starring Christopher Todd, Monica Stagg, Stephanie Ritz, Joniruth White, John Walter, Leah Palen, Larry Whitfield, Rodney Rowland, Richard Castaldo, Henry Pincus, Marguerita Fahrer, Christopher Dinerman, John Limpert, Pasquale Gaeta, Cory Einbinder, Gabrielle Corsaro, Laura Yengo and Peter Cossack. Directed by Thomas Mazziotti.

Andor Season 2

It’s easy to imagine the longer, more fleshed out version of Andor, particularly once Alan Tudyk’s sassy police droid arrives to remind why he was the best part of Rogue One. Something was definitely lost in the transition, but as Andor reminds us with every unanswered question and desperate fate, that’s life.

The making of the original Star Wars is replete with stories of the obstacles George Lucas and his team of intrepid craftsmen had to overcome in its realization, and the inspired solutions and compromises they were forced into which became the texture of the film its admirers adored and memorized. (And woe be to anyone who challenges those compromises later). Armed with a nearly $300 million budget, Tony Gilroy did not have anywhere near the same limitations forced on him when he began Andor, the inspired prequel to Rogue One: A Star Wars Story and Lucas’ own film detailing the earliest days of the Rebel Alliance and its own compromises (moral and otherwise) inherent in standing up to authoritarian tyranny. Ostensibly focusing on the journey of smuggler-turned-rebel Cassian Andor (Luna), Gilroy transmogrified Andor into a multi-faceted view of life under fascism and the cost, and value, of standing up to it, the beginning of a five-season plan to march through individual years of Andor’s, and the galaxy’s, life in the mixture of glacial and surprisingly immense change existence is made of.

Looking back on both the success of the first season and the multiple years of writing, production and post-production it took to get there Gilroy realized even the immense of resources Disney and Lucasfilm had given him weren’t going to be able to overcome the immutable march of time and twenty years of production was going to be bit much even for his grand design. So, like his Star Wars-ian forebears, Gilroy compromised, reducing his five-year plan to one as he dips, an episode at a time, into a year of the galaxy’s life to check on events before jumping forward a year to show how they’ve changed and mutated.

It's a noted change from the first seasons’ slow burn which built tension through character, conversation by conversation and moment by moment until there was no option but an explosion. Andor Season 2 offers a similar cadence -- particularly in the growth of its contrasting couples Andor and Bix (Arjona) and Dedra (Gough) and Syril (Soller) -- but by design must also stop from time to time for Andor to find himself in the middle of a riot or attempting to spirit Mon Mothma (O’Reilly) out of the capital as Imperial agents close in. It makes for a stop-and-start dynamic which compliments the growing tension of the first season without repeating it and keeping centered on its core components as much of the flavor is pushed away to make room for necessity. Andor has places to go and things to do.

Which doesn’t mean it can’t faff about when the mood takes, particularly among Gilroy’s particular episodes setting up the season which see the wedding of Mon’s rebellious daughter to a criminal banker while Andor is temporarily marooned on a familiar jungle planet after a TIE-fighter heist goes wrong. These are the episodes which most feel like the previous season, setting aside plot progression in favor of character detail. Andor may want to be part of the Rebellion but he has no idea how to do it and is quickly realizing no one around him does either. His only fortune is that the people aligned against are equally in the dark.

It’s both precious and previous and gives only the slightest hint as to what is to come.

Which is not useless; even as he flits from year-to-year Gilroy table sets to prepare for the inevitable but also uses those moments to relish in the absurd. As thrilling, heartfelt and commentative on the present moment as Andor is, there may nothing in it better than the galaxy’s most uncomfortable dinner with Syril, his mother and Dedra. The nexus of such concentrated misanthropy is clearly a treat for Gilroy who revels most in his vilest creations’ statements of selfishness and cruelty where personal aggrandizement is placed above humanity, from bureaucratic Himmler stand-in Major Partagaz (Lesser) to the returning Director Krennic (Mendelsohn) who is given prose poems of malevolent intent.

And all of it terribly real. Not just because we can easily believe that if there were a Galactic Empire far, far away it would be staffed by exactly such individuals – the same people exist today in the here and now and are trying to do very similar things for very similar reasons – but because Gilroy makes certain even his most diabolical creations have real, and relatable, inner lives. Dedra loves for real and for the same reasons we do, making her cruelties all the worse as she is unwilling or unable to see that truth of what she is doing to others, but her heartbreak as understandable as our nearest and dearest kin. The greatest trick the devil ever pulled is not making the world think he didn’t exist, it’s tricking us into feeling the pain of the remorseless.

As the story moves inevitably forward, like life itself it begins to speed up until those movements between the notes which have given it shape must be cast aside to make room for the crescendo. In some ways the decision to focus on three days of Andor’s life and then jump forward a year adds strength to the progression a more leisurely pace could have accidentally sapped. The long-term consequence of choices and decisions are immediately felt. The plot to steal resources from the peaceful planet of Ghorman while cutting it off from the rest of the galaxy is moved from what could have been a multi-year arc to a stark before and after picture as Andor and company visit the world at different stages to aid its nascent guerilla uprising. It’s exactly the sort of dramatic escalation the prolonged version of the story may have neutered or at least lessened. By the same token, Bix’s psychological recovery from torture at Dedra’s hands takes years, but is quickened to the point where its feeling remains without protracted or repetitive elements.

There’s a price to be paid for that momentum shift. As events accelerate and plot takes over character is forced to take a back seat, leaving life changing decisions and occurrences which once would have been fodder for intense dissection to be pushed to the margins and occasionally shrugged at. After years of sitting at the center of Rebel growth, living eternally in the same paranoia he benefits from, spymaster Luthen Rael (Skarsgård) is gradually sidelined in favor of the more orderly military operation will meet in “Star Wars.” An operation Mon Mothma, after years of hiding her activity within the political canyons of the Empire, finds herself leading. What does Luthen think of the outcome he foresaw when it finally reaches him? Or Mon and her family of her true self when it is revealed and leaves them behind? We’ll never know; suddenly, for them and for us, there’s not enough time.

Is it a compromise? Or is it an accidental revelation of the series’ ideal form?

We’ll never know, an argument can be made for both. It’s easy to imagine the longer, more fleshed out version of Andor, particularly once Alan Tudyk’s sassy police droid arrives to remind why he was the best part of Rogue One. Something was definitely lost in the transition, but as Andor reminds us with every unanswered question and desperate fate, that’s life.

9.5 out of 10

Starring Diego Luna, Stellan Skarsgård, Genevieve O’Reilly, Elizabeth Dulau, Adria Arjona, Denise Gough, Kyle Soller, Anton Lesser and Ben Mendelsohn. Written by Tony Gilroy, Beau Willimon, Dan Gilroy and Tom Bissell.

Rule Breakers

Several decades deep into the 21st century, a time period seemingly far enough into the future that multiple films over the last fifty years have used at the future point of seeming utopia or at least massive futurism, and the reality is we are still shackled with the faults and weaknesses bygone eras which seem like they will never leave us. In large portions of the world not only are basic necessities like food, water, and shelter still daily struggles to achieve (and access to power or technology a frequent luxury) but education remains restricted to select groups based on ancient custom. Entire regions continue to deny themselves the best chances at growth to keep entire genders cut off from the worlds they live in.

Several decades deep into the 21st century, a time period seemingly far enough into the future that multiple films over the last fifty years have used at the future point of seeming utopia or at least massive futurism, and the reality is we are still shackled with the faults and weaknesses bygone eras which seem like they will never leave us. In large portions of the world not only are basic necessities like food, water, and shelter still daily struggles to achieve (and access to power or technology a frequent luxury) but education remains restricted to select groups based on ancient custom. Entire regions continue to deny themselves the best chances at growth to keep entire genders cut off from the worlds they live in.

But as long as the rules have been in place, there have been people to break them.

The story of Roya Mahboob (Boosheri) has become one of the standouts of that philosophy. One of the first self-made women technology CEOs in Afghanistan, Mahboob burst onto the international stage when she and her group of self-taught high school engineers began entering global robotics contests. With their robot mine-sweeper they sought to enrich their lives and those of their neighbors, looking to build something for their home with their ambition rather than leave it behind. But arrayed against them was not just the walled in morays of their homeland, Taliban ruled Afghanistan which did not believe in education for girls, but the realities of poverty, bureaucracy, and removal from resources which the developed world still isn’t ready to do something about.

Award winning documentary filmmaker Bill Guttentag’s straightforward adaptation of Mahboob’s story doesn’t bring new answers to those questions, or particular insight into Mahboob’s struggle beyond the obvious. But it doesn’t really have to either. The struggle itself is real, albeit heavily ‘based on’ Mahboob’s life as opposed to directly transcribing it, and that is enough to lend real power to its reenactment even if the staging is all very familiar. The man who helped bring the “Masterclass” series to us knows how to structure an inspirational moment and isn’t going to change outlook here. The strictures around the need for self-belief and determination are as prevalent as any studio underdog tale, it’s the guiding thesis of modern inspirational storytelling outside of the faith-based distributors. The dichotomy is more striking in Rule Breakers as it is the faith of others for outside rules which are largely holding the girls back, and it is by turning inwards that a path to victory is possible. More importantly, the film doesn’t need some outrageously original format if the foundations are strong. And they are.

They’re built almost entirely around Roya’s team, from her less forceful friend Esin to her curious co-engineers who need convincing of their path. It’s not just the facts of their story but the easy camaraderie and excitement for the adventure they are undertaking which gives Rule Breakers any sort of spirit or life. There’s no mistaking where the focus is on a film whose main character is based on one of the producers and whose family member co-wrote the screenplay, which is an issue as Roya is most alive and well-defined within the context of her team rather than an isolated individual carrying the weight of expectations on her shoulder. Some of that is by design in good ways as her teammates bring themselves up to the bar that’s been set for them (albeit frequently off screen), but some in bad old ways of needing a central focus in a story which is ultimately more diffuse.

None of which detracts from the film’s strengths, both in its themes, sentiment, and execution. Rule Breakers is exactly what it says on the tin, a satisfying and uplifting tale of struggle against the forces it seems like we should have left behind by now. Hopefully one day we will, as long as more rule breakers follow in Roya Mahboob’s path.

Starring Nikohl Boosheri, Ali Fazal, Amber Afzali, Nina Hosseinzadeh, Sara Malal Rowe and Phoebe Waller-Bridge. Directed by Bill Guttentag.

Captain America: Brave New World

It’s time for a reset. For Captain America, for Sam Wilson, for Marvel, for everyone. After the story and character conclusion of Avengers: Endgame the continued joint story structure of Marvel has looked around for a new focus to push itself into the future and in the process spread itself progressively thinner through ever more films and television series. What did it all mean? Where was it all going? No one seemed to know and nothing seemed to be sticking. Looking back over the last several years of choices and directions, director Julius Onah (The Cloverfield Paradox) and a very game Anthony Mackie have picked up the ball and attempted to start making some headway.